In the sixteenth century, the central part of the magnificent Baths of Diocletian were converted into a church by Michelangelo. The church, dedicated to the holy angels and martyrs, gives us a rare glimpse at the scale and majesty of a Roman bathhouse.

The Baths of Diocletian

The Baths of Diocletian were some of the most sumptuous baths in Rome. They could accommodate some three thousand visitors.

The complex was built in 306 AD following the model of the Baths of Trajan with a caldarium (hot water bath), tepidarium (warm water), frigidarium (cold water) and natatio (swimming pool) built along a central axis. The baths covered an area of more than eleven hectares (27 acres).

The baths fell into disuse in the sixth century after the Goths cut off the water supply. For centuries the baths were plundered first by invading barbarians and later by the Romans themselves who used the ruins as building materials for the construction of new buildings. Nevertheless, a large part of the structure is still intact, albeit devoid of any ornamentation.

The Seven Archangels

After Antonio Lo Duca, a sixteenth-century Sicilian friar, discovered a picture of Mary with the seven archangels, he became obsessed with the veneration of the angels. He claimed to have seen a vision of the angels appearing in the Baths of Diocletian, and wanted to turn the ancient bath complex into a church dedicated to the seven angels.

After fruitlessly campaigning for twenty years, he finally got his wish in 1561 when Pope Pius IV entrusted Michelangelo Buonarotti with the task of building a church inside the ruins of the ancient bath complex.

Construction and remodeling

Michelangelo was already eighty-six years old at the time, and this would be his last architectural project. He opted for a floor plan in the shape of a Greek cross, with a nave and transept of equal length. He incorporated the church building into the former frigidarium, leaving the Roman structure more or less intact. By the time of Michelangelo’s death in 1564 the church was still unfinished, but his plans were implemented by one of his pupils, Giacomo del Duca, who happened to be a nephew of Antonio Lo Duca.

In the eighteenth century, Michelangelo’s design was modified by Luigi Vanvitelli, who moved the main altar and changed the orientation so that the original transept is now the nave. The Neapolitan architect also added decorative elements such as plasterwork, and he added eight more columns identical in appearance to the original Roman ones. In addition, Vanvitelli also built a new front facade.

The Church

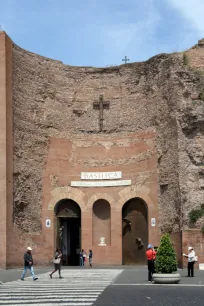

Vanvitelli’s facade was removed in 1911 so that the entrance facing Piazza della Repubblica looks again unadorned as was intended by Michelangelo. The current front facade is actually an exedra that was part of the caldarium. The bronze doors are modern and were created by Igor Mitoraj, a Polish sculptor.

The circular vestibule (the former tepidarium) holds a statue of St. Bruno, created by the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. The church was assigned to the Carthusian Order, which was founded by the saint. The vestibule has a beautiful coffered dome ceiling.

Nave and transept

Once inside the nave, one gets an idea of the astonishing size of the ancient Roman baths. The church, which only occupies the central part of the baths, is over ninety meters wide. The cross-vaulted ceiling over the transept is twenty-eight meters above the floor, which was elevated more than two meters so as to protect the church against rising moisture.

As a result, only about fourteen meters of the seventeen-meter tall columns are visible. The original Roman bases are hidden under the floor and were replaced by reproductions. The massive red granite columns, the largest in Rome, measure 1.6 meters in diameter. Only the eight central columns are from the Roman era. The others are skillful imitations in plaster; it’s surprisingly hard to tell them from the originals.

Paintings

The painting of the seven archangels and Mary that inspired Antonio Lo Duca is now the main altarpiece. The painting is framed with sculptures of angels. The twelve large paintings on the walls were placed here in 1727. They were intended for the St. Peter’s Basilica, but the high humidity damaged the paintings, so they were replaced by mosaics and transferred to here.

Linea Clementina

On the floor in the right transept you can see the Linea Clementina, the meridian of Rome. Until 1846 the meridian was used by Roman citizens to set the time. A small opening in the roof causes sunlight to fall on the line right at noon.

The meridian was created in 1702 by the astronomer Francesco Bianchini on the behest of Pope Clement XI, as part of a project to improve the accuracy of the calendar. Along the line are marks indicating the zodiac signs.

Millennium Organ

The great mechanical organ of the Santa Maria degli Angeli was built by Barthèlèmy Formentelli. It was a present from Roman citizens to Pope John Paul II on the occasion of the new millennium, hence it is known as the millennium organ. The organ has a total of 5,400 pipes housed in a casing that measures twelve meters high and eleven meters wide.